Getting Started With Arduino and Ethernet

by pmdwayhk in Circuits > Arduino

4340 Views, 0 Favorites, 0 Comments

Getting Started With Arduino and Ethernet

Your Arduino can easily communicate with the outside world via a wired Ethernet connection. However before we get started, it will be assumed that you have a basic understanding of computer networking, such as the knowledge of how to connect computers to a hub/router with RJ45 cables, what an IP and MAC address is, and so on. Furthermore, here is a good quick rundown about Ethernet.

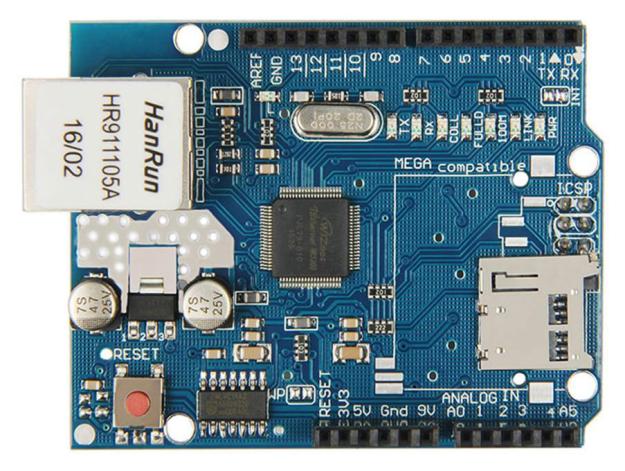

You will need an Arduino Uno or compatible board with an Ethernet shield that uses the W5100 Ethernet controller IC (pretty much all of them) as per the image.

Furthermore you will need to power the board via the external DC socket – the W5100 IC uses more current than the USB power can supply. A 9V 1.5A plug pack/wall wart will suffice.

Finally - the shields does get hot – so be careful not to touch the W5100 after extended use. In case you’re not sure – this is the W5100 IC.

Once you have your Ethernet-enabled Arduino, and have the external power connected – it’s a good idea to check it all works. Open the Arduino IDE and select File > Examples > Ethernet > Webserver. This loads a simple sketch which will display data gathered from the analogue inputs on a web browser. However don’t upload it yet, it needs a slight modification.

You need to specify the IP address of the Ethernet shield – which is done inside the sketch. This is simple, go to the line:

IPAddress ip(10,1,1,77);

And alter it to match your own setup. For example, in our home the router’s IP address is 10.1.1.1, the printer is 10.1.1.50 and all PCs are below …50. So I will set my shield IP to 10.1.1.77 by altering the line to:

byte mac[] = { 0xDE, 0xAD, 0xBE, 0xEF, 0xFE, 0xED };

However if you only have one shield just leave it be. There may be the very, very, statistically rare chance of having a MAC address the same as your existing hardware, so that would be another time to change it.

However if you only have one shield just leave it be. There may be the very, very, statistically rare chance of having a MAC address the same as your existing hardware, so that would be another time to change it.

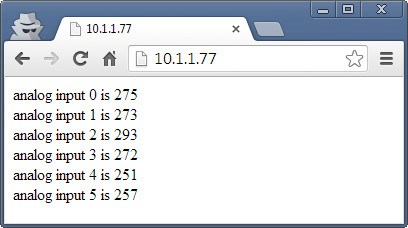

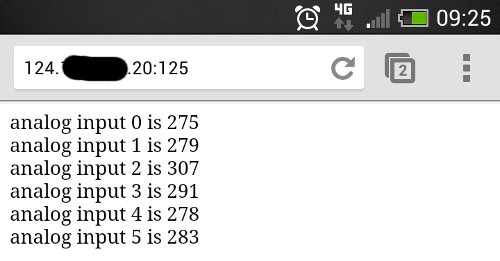

Once you have made your alterations, save and upload the sketch. Now open a web browser and navigate to the IP address you entered in the sketch, and you should be presented with something similar to the image.

What’s happening?

The Arduino has been programmed to offer a simple web page with the values measured by the analogue inputs. You can refresh the browser to get updated values.

At this point – please note that the Ethernet shields use digital pins 10~13, so you can’t use those for anything else. Some Arduino Ethernet shields may also have a microSD card socket, which also uses another digital pin – so check with the documentation to find out which one.

Nevertheless, now that we can see the Ethernet shield is working we can move on to something more useful. Let’s dissect the previous example in a simple way, and see how we can distribute and display more interesting data over the network. For reference, all of the Ethernet-related functions are handled by the Ethernet Arduino library. If you examine the previous sketch we just used, the section that will be of interest is:

for (int analogChannel = 0; analogChannel < 6; analogChannel++)

{ int sensorReading = analogRead(analogChannel); client.print("analog input "); client.print(analogChannel); client.print(" is "); client.print(sensorReading); client.println("<br />"); } client.println("<html/>");

Hopefully this section of the sketch should be familiar – remember how we have used serial.print(); in the past when sending data to the serial monitor box? Well now we can do the same thing, but sending data from our Ethernet shield back to a web browser – on other words, a very basic type of web page.

However there is something you may or may not want to learn in order to format the output in a readable format – HTML code. I am not a website developer (!) so will not delve into HTML too much.

However if you wish to serve up nicely formatted web pages with your Arduino and so on, here would be a good start. In the interests of simplicity, the following two functions will be the most useful:

<p>client.print(" is ");</p>Client.print (); allows us to send text or data back to the web page. It works in the same way as serial.print(), so nothing new there. You can also specify the data type in the same way as with serial.print(). Naturally you can also use it to send data back as well. The other useful line is:

<p>client.println("<br/>");</p>which sends the HTML code back to the web browser telling it to start a new line. The part that actually causes the carriage return/new line is the

<br/>

which is an HTML code (or “tag”) for a new line.

So if you are creating more elaborate web page displays, you can just insert other HTML tags in the client.print(); statement. If you want to learn more about HTML commands, here’s a good tutorial site.

Finally – note that the sketch will only send the data when it has been requested, that is when it has received a request from the web browser.

Accessing Your Arduino Over the Internet

So far – so good. But what if you want to access your Arduino from outside the local network?

You will need a static IP address – that is, the IP address your internet service provider assigns to your connection needs to stay the same. If you don’t have a static IP, as long as you leave your modem/router permanently swiched on your IP shouldn’t change. However that isn’t an optimal solution.

If your ISP cannot offer you a static IP at all, you can still move forward with the project by using an organisation that offers a Dynamic DNS. These organisations offer you your own static IP host name (e.g. mojo.monkeynuts.com) instead of a number, keep track of your changing IP address and linking it to the new host name. From what I can gather, your modem needs to support (have an in-built client for…) these DDNS services.

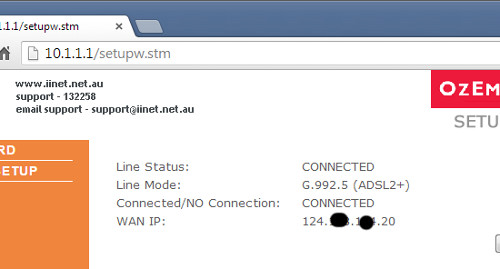

As an example, two companies are No-IP andDynDNS.com. Please note that I haven’t used those two, they are just offered as examples. Now, to find your IP address… usually this can be found by logging into your router’s administration page – it is usually 192.168.0.1 but could be different. Check with your supplier or ISP if they supplied the hardware. For this example, if I enter 10.1.1.1 in a web browser, and after entering my modem administration password, the following screen is presented as per the image.

What you are looking for is your WAN IP address, as you can see in the image above. To keep the pranksters away, I have blacked out some of my address.

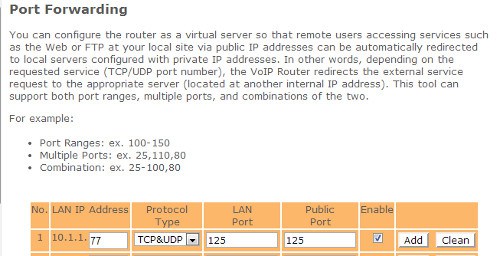

The next thing to do is turn on port-forwarding. This tells the router where to redirect incoming requests from the outside world. When the modem receives such a request, we want to send that request to the port number of our Ethernet shield. Using the:

EthernetServer server(125);

function in our sketch has set the port number to 125. Each modem’s configuration screen will look different, but as an example here is one in the image.

So you can see from the line number one in the image above, the inbound port numbers have been set to 125, and the IP address of the Ethernet shield has been set to 10.1.1.77 – the same as in the sketch.

After saving the settings, we’re all set. The external address of my Ethernet shield will be the WAN:125, so to access the Arduino I will type my WAN address with :125 at the end into the browser of the remote web device, which will contact the lonely Ethernet hardware back home.

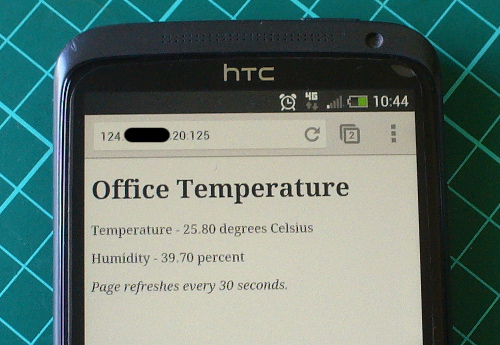

Furthermore, you may need to alter your modem’s firewall settings, to allow the port 125 to be “open” to incoming requests. Please check your modem documentation for more information on how to do this. Now from basically any Internet connected device in the free world, I can enter my WAN and port number into the URL field and receive the results. For example, from a phone when it is connected to the Internet via LTE mobile data.

So at this stage you can now display data on a simple web page created by your Arduino and access it from anywhere with unrestricted Internet access. With your previous Arduino knowledge you can now use data from sensors or other parts of a sketch and display it for retrieval.

Displaying Sensor Data on a Web Page

As an example of displaying sensor data on a web page, let’s use an inexpensive and popular temperature and humidity sensor – the DHT22. You will need to install the DHT22 Arduino library which can be found on this page. If this is your first time with the DHT22, experiment with the example sketch that’s included with the library so you understand how it works.

Connect the DHT22 with the data pin to Arduino D2, Vin to the 5V pin and GND to … GND. Now for our sketch – to display the temperature and humidity on a web page. If you’re not up on HTML you can use online services such as this to generate the code, which you can then modify to use in the sketch. In the example below, the temperature and humidity data from the DHT22 is served in a simple web page:

#include "SPI.h"

#include "Ethernet.h"// for DHT22 sensor #include "DHT.h" #define DHTPIN 2 #define DHTTYPE DHT22

// Enter a MAC address and IP address for your controller below. // The IP address will be dependent on your local network: byte mac[] = { 0xDE, 0xAD, 0xBE, 0xEF, 0xFE, 0xED }; IPAddress ip(10,1,1,77);

// Initialize the Ethernet server library // with the IP address and port you want to use // (port 80 is default for HTTP): EthernetServer server(125); DHT dht(DHTPIN, DHTTYPE);

void setup() { dht.begin(); // Open serial communications and wait for port to open: Serial.begin(9600); while (!Serial) { ; // wait for serial port to connect. Needed for Leonardo only } // start the Ethernet connection and the server: Ethernet.begin(mac, ip); server.begin(); Serial.print("server is at "); Serial.println(Ethernet.localIP()); }

void loop() { // listen for incoming clients EthernetClient client = server.available(); if (client) { Serial.println("new client"); // an http request ends with a blank line boolean currentLineIsBlank = true; while (client.connected()) { if (client.available()) { char c = client.read(); Serial.write(c); // if you've gotten to the end of the line (received a newline // character) and the line is blank, the http request has ended, // so you can send a reply if (c == 'n' && currentLineIsBlank) { // send a standard http response header client.println("HTTP/1.1 200 OK"); client.println("Content-Type: text/html"); client.println("Connection: close"); // the connection will be closed after completion of the response client.println("Refresh: 30"); // refresh the page automatically every 30 sec client.println(); client.println("<!DOCTYPE HTML>");

client.println("<html>");

// get data from DHT22 sensor float h = dht.readHumidity(); float t = dht.readTemperature(); Serial.println(t); Serial.println(h);

// from here we can enter our own HTML code to create the web page client.print("<head><title>Office Weather</title></head><body></h1>Office temperature - ");

client.print(t); client.print(" degrees Celsius</p>");

client.print("<p>Humidity - ");

client.print(h); client.print(" percent </p>");

client.print("<p><em>Page refreshes every 30 seconds<<em></p></body></html>.");

break; } if (c == 'n') { // you're starting a new line currentLineIsBlank = true; } else if (c != 'r') { // you've gotten a character on the current line currentLineIsBlank = false; } } } // give the web browser time to receive the data delay(1); // close the connection: client.stop(); Serial.println("client disonnected"); } }

It is a modification of the IDE’s webserver example sketch that we used previously – with a few modifications. First, the webpage will automatically refresh every 30 seconds – this parameter is set in the line:

client.println("Refresh: 30"); // refresh the page automatically every 30 sec

… and the custom HTML for our web page starts below the line:

// from here we can enter our own HTML code to create the web page

You can then simply insert the required HTML inside client.print() functions to create the layout you need.

Finally – here’s an example screen shot of the example sketch at work.

So there you have it, another useful way to have your Arduino interact with the outside world.

This post is brought to you by pmdway.com – everything for makers and electronics enthusiasts, with free delivery worldwide.